Australia's inflation problem is back

Or did it never go away?

I hope all my Australian readers had a great Australia Day long weekend — a holiday that, despite periodic calls to change the date, remains deeply popular with the voting public.

I wish I had some good news to share today. But if the latest spending and inflation data are any indication of what's to come, then you may not be getting much relief in terms of your weekly shop or mortgage this year.

Let's jump right in. First, demand is still running too hot. The official Monthly Household Spending Indicator for November came in at a very strong 1.0% month-on-month, with services spending growth especially robust. That's important, because services spending tends to be more indicative of demand pressures rather than supply-side disruptions, which can be more relevant for goods.

If households were feeling the pinch from tighter monetary policy, you might expect to see it in discretionary services first. But we're just not seeing it.

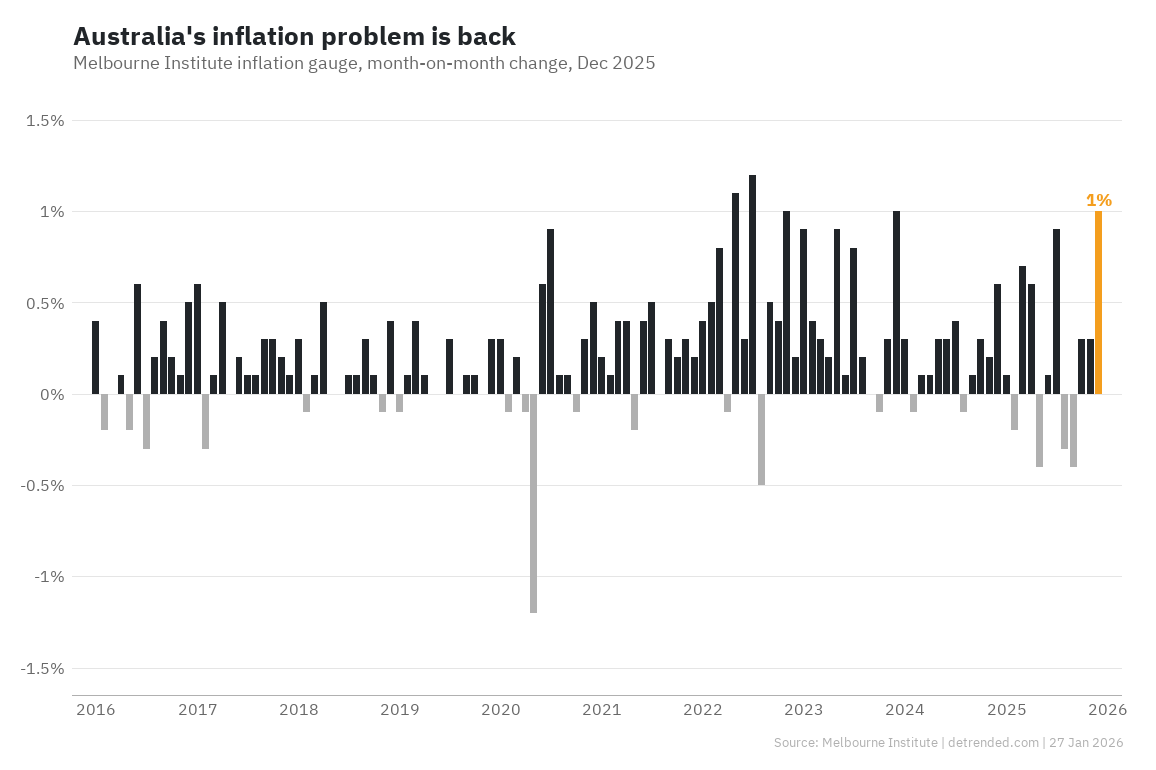

Second, the Melbourne Institute's inflation gauge jumped 1.0% in December from the prior month, a 20-month high that annualises to a rate of 12%. Of course, such a big jump deserves some scepticism and, as with the spending data above, is likely to have a lot of seasonal noise. They're both adjusted for Black Friday and Christmas but the sales period has become increasingly diffuse, making the summer data less reliable than it used to be.

Still, we shouldn't be getting readings this high this late in the Reserve Bank of Australia's (RBA) tightening cycle, suggesting that it may have taken its foot off the brake a little too soon (it has cut the cash rate three times since December 2024).

Moreover, the strong growth matches other data released well before the holiday period. For example, the Gross National Expenditure deflator rose 0.8% in the September quarter. The GNE deflator strips out trade (commodity price volatility matters for Australia given the large exposure to it), so it captures domestic price pressures—and those pressures are running hot. Unit labour costs are also still growing at around 5% annually, well above the pre-pandemic average. With productivity growth anaemic, wage pressures are passing straight through to prices.

That's not a seasonal story. That's a policy story. And while the RBA deserves some blame, it has received zero support from profligate state and federal politicians who are still worsening Australia's fiscal position. The recent OECD Economic Survey of Australia and IMF's World Economic Outlook update both flagged Australia's fiscal stance as a concern, with the debt-to-GDP ratio on a "steep upward path".

Debt-financed government spending adds directly to demand that monetary policy must then work against. Unless the RBA is willing to fully offset it with tighter policy — and so far it hasn't been — inflation is the inevitable release valve.

The RBA meets again in a week. I'm not expecting a rate hike (and neither are markets), but I'm increasingly sceptical we'll see further cuts this year. The central bank will want to see sustained evidence that inflation is back under control before moving again, and the current data doesn't provide that.

For anyone hoping for mortgage relief in 2026: don't hold your breath!