Japan's risky bet

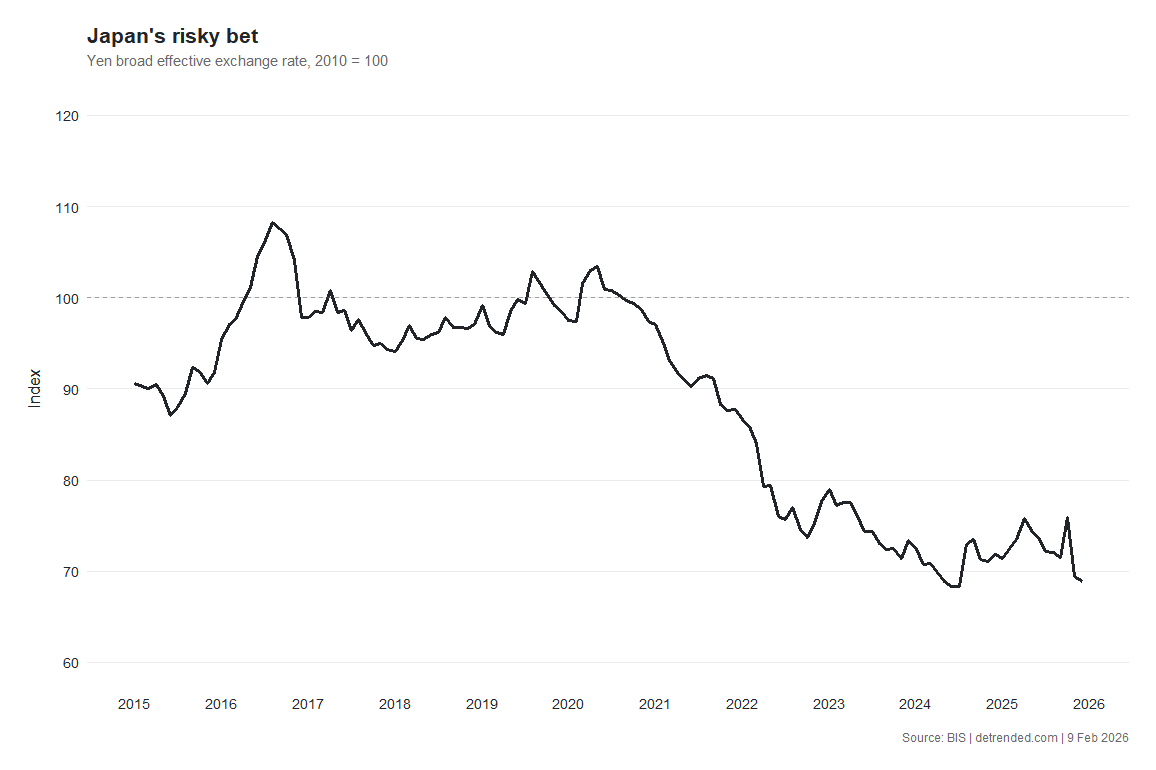

Japan's ruling party won a supermajority promising massive stimulus and tax cuts, but the yen's slide to near all-time lows suggests markets are sceptical the debt math works.

Japan's ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), led by its first female Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, secured a resounding two-thirds majority in the lower house and therefore control of all-important parliamentary committees in yesterday's snap election.

To think that just eight months ago the LDP had lost its parliamentary majority for the second time in fifteen months under former Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, it has been quite the turnaround in fortunes. And Takaichi deserves plenty of credit; dubbed an "ultra-conservative" by some, she has honed in on hotspots from defence and immigration to the rising cost of living, all while maintaining a down-to-earth and relatable persona.

But while voters are eating up her policies, which include a platform of massive stimulus spending and tax cuts, markets are more cautious. The yen has weakened to ~¥157 against the US dollar, which is close to all-time lows. Since the start of 2021, the yen's purchasing power has fallen 33% against a trade weighted index of currencies.

Japan's situation is unusual mainly because higher yields haven't translated into a stronger yen. That's because higher yields only prop up a currency when they're signalling better returns; if they're signalling more inflation or more risk, which markets may be starting to price in, the currency can still depreciate.

Japan's government debt sits at around 230% of GDP, among the highest in advanced nations, and debt servicing costs are expected to rise 10.8% year-on-year. The Bank of Japan (BoJ) – the central bank – has been trying to normalise monetary policy since 2024 by tapering its bond purchases, while the central government is planning to issue more debt than ever before.

The vast majority of Japan's public debt is owned locally, whether by the BoJ, pension funds, banks, or insurers. And this is where Japan's risky bet comes into it: a decade ago, the Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF) held 60% of its portfolio in Japanese government bonds. Then the Abe government prodded GPIF to shift into equities, dropping domestic bond holdings to 25% while increasing domestic and foreign stock allocations to 25% each, with the remaining 25% in foreign bonds. This reduced a large source of government bond demand, which was filled by the BoJ, monetising the deficit while GPIF bought higher-yielding stocks instead.

Essentially, Japan's public sector is operating as a kind of sovereign wealth fund built on debt. The government issues bonds and the BoJ snaps them up with printed yen. Separately, GPIF allocates a large share of its portfolio to unhedged foreign assets under its policy mix, leaving Japan's consolidated public sector with heavy exposure to foreign-currency risk assets alongside very large yen liabilities. If domestic rates rise, debt service worsens; if the yen strengthens, the yen value of foreign assets falls; and if global equities drop, the asset side takes a hit.

So far, it has worked out brilliantly for the government (the same can't be said for Japan's households!). Yields are still low in Japan relative to other countries, and the depreciating yen has provided the public sector with large mark-to-market gains.

Takaichi's electoral strategy is essentially a doubling down on this model: more spending, potential tax cuts, and the explicit acceptance of yen weakness as being beneficial. If this works—i.e., if nominal growth accelerates enough to stabilise the debt dynamics—Japan will have pulled off something remarkable. If it doesn't, the unwind could be spectacular.