The RBA keeps making the same mistake

From running too tight to cutting too early, the Reserve Bank of Australia keeps making the same monetary mistake.

You're probably all sick of my Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) posts by now. I'll give it a rest soon, but Bullock said something last week that's too revealing to ignore. Specifically, her response to questions about public demand contributing to the uptick in measured inflation:

"Mathematically, you're right. Public demand expenditure and private sector, all of that adds to demand. That's logical. It's mathematical. That's what happens. It's factual. It's not an opinion. It's not a judgement, it's a fact."

Bullock is right about the arithmetic: total spending is public spending plus private spending. But that's an accounting identity, not a theory of inflation. It tells you the composition of spending, not what sets the economy's total nominal spending in the first place. Saying government spending "adds to demand" because it appears in the equation is like saying umbrellas cause rain.

If Canberra spends more, the RBA doesn't have to just shrug and accept higher inflation; it can—and should—lean harder on policy to keep economy-wide nominal spending from running hot. If inflation sits above the its target for a prolonged period, it's not because of an identity on a blackboard; it's because monetary policy didn't lean in hard enough, soon enough.

To be clear, there's a legitimate critique of expansionary fiscal policy, in that when done poorly or when the economy is close to its ability to produce it can crowd out private sector activity and therefore drag on productivity. But that's a real-economy critique, not a get-out-of-jail-free card for runaway inflation. Over time, inflation is what happens when the central bank lets nominal spending run ahead of what the economy can produce. The RBA should look through genuine one-off shocks, but the higher trend only sticks around if policy lets it.

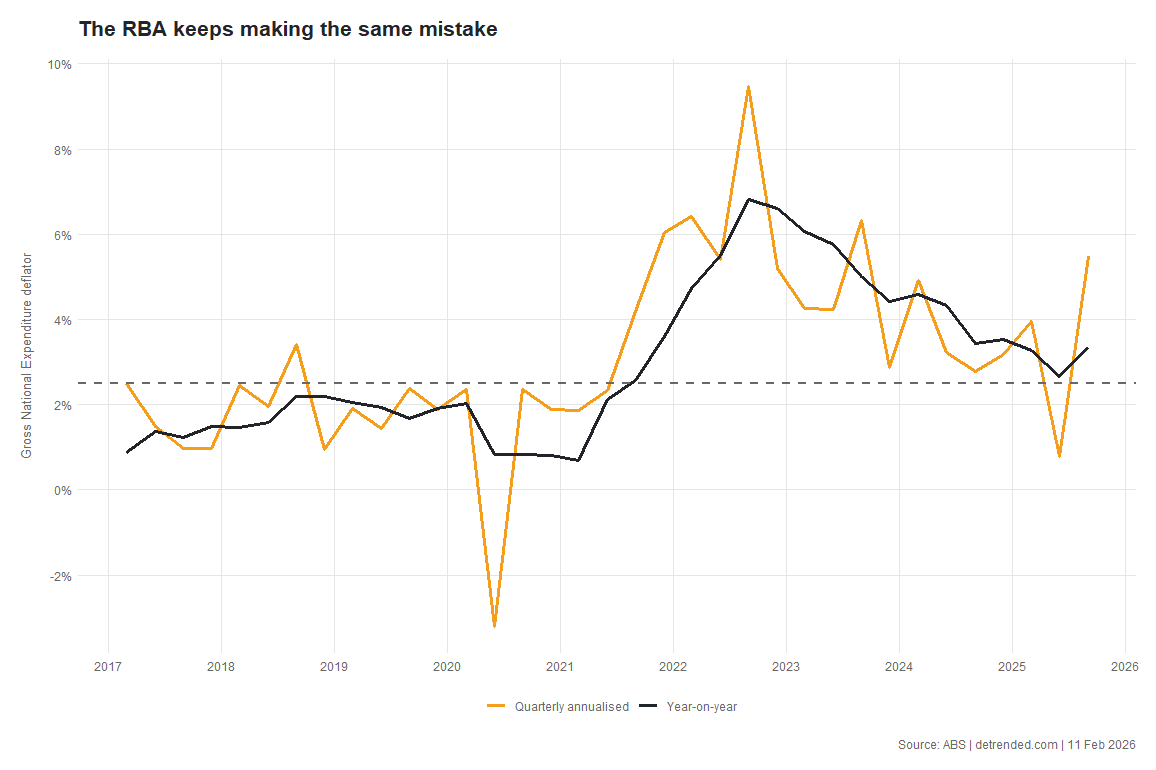

One useful check is to look at the national account deflators around domestic spending (e.g. the gross national expenditure, or GNE, deflator), which give you a read on domestic price pressures that aren't dominated by volatile commodity prices. It's not a perfect inflation measure – deflators can move with compositional changes – but it's still a decent check for the 'it's all fiscal' story. If the GNE deflator is persistently running hot, monetary policy is too loose relative to the inflation objective; if it's persistently weak, policy is too tight.

This isn't controversial monetary economics. The Bank of England doesn't blame National Health Service spending for inflation in the UK. The US Fed doesn't hold a press conference about Medicare spending. They might complain that fiscal policy makes their job more difficult, but they don't pretend it takes away their ability to control it.

Bullock's framing suggests otherwise. By repeatedly emphasising that government spending "adds to demand", she's implying fiscal policy has an independent effect on nominal spending to which the RBA must react. But if the RBA is adjusting monetary policy in response to fiscal policy, then by definition the RBA is still in control.

The chart above shows a long stretch of the RBA being behind the curve: first too tight, then too loose. From 2017 to 2020, the RBA systematically ran the GNE deflator below the 2.5% target midpoint. Then came the 2021-22 overshoot when loose monetary policy drove the GNE deflator above 6%. And most recently, the RBA cut rates in February 2025 when the year-on-year GNE deflator was still running above 3% annually, right as electricity rebates temporarily made the numbers look nicer than the underlying reality. That 'good news' was always going to wash out, and it did.

State and federal spending didn't cause the post-pandemic inflation spike, and government spending isn't preventing the RBA from hitting its target now. More difficult? Sure. But the problem is the RBA keeps making the same mistake: reacting to short-term noise instead of maintaining steady nominal spending growth.

Bullock can say fiscal policy is making her job harder. But she can't say government spending mathematically "adds to demand" and also say 'don't worry, we'll offset it with higher rates' without admitting the obvious: the RBA is still choosing the nominal path, and therefore, the rate of inflation.

Either the RBA controls the nominal side of the economy, or it doesn't. You can't have it both ways.

P.S. I'm travelling all next week so posting will be sporadic, if at all.