The RBA's false dawn

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) meets today to make its first decision of 2026. Six months ago it was cutting rates; today, markets are pricing in a full 25 basis point hike, and all four major banks are forecasting the same. If it happens as expected, it'll be the RBA's first rate increase in over two years and implicitly an admission that the easing cycle it launched in February 2025 was premature.

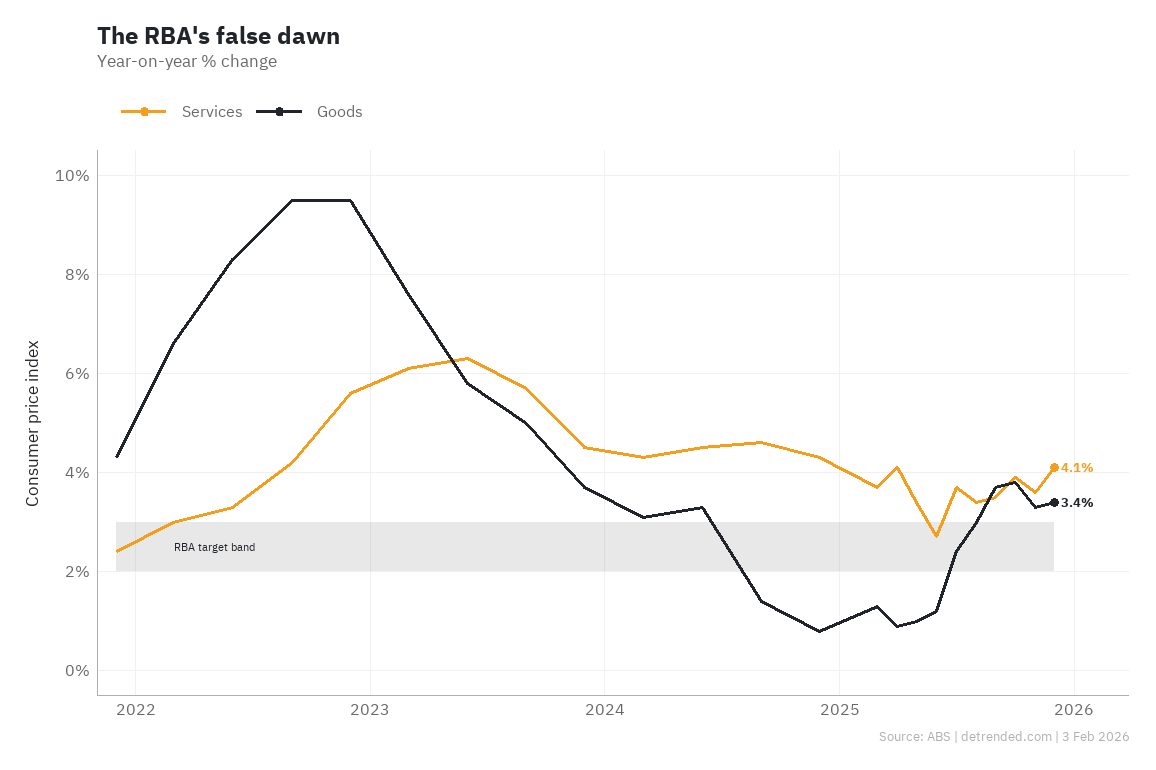

If you want the detailed version, last week's pre‑inflation note is here; otherwise, the chart below tells most of the story.

Essentially, goods disinflation was temporary, while services inflation stayed sticky. Electricity rebates from the Commonwealth and states mechanically pulled energy prices down, while global goods deflation (normalised supply chains, soft oil prices, and a deflationary China exporting cheaper manufactures) did the rest.

But as those "cost of living" rebates and global effects washed out of the annual comparison and the RBA's rate cuts took hold, goods inflation bounced right back to 3.4% and services inflation—which includes the bulk of the domestic, labour-intensive stuff—accelerated. The brief dip to 2.7% in June 2025 was the false dawn that probably gave the RBA confidence to keep cutting, which was a big mistake.

The backdrop makes it worse. Government demand (government consumption + public investment) is now 28.9% of GDP, only fractionally below the June 2020 pandemic-era high. In other words, the RBA is trying to cool demand with one hand while fiscal settings are still pulling the other way.

But the characteristics of the spending is also problematic: the growth hasn't been from a surge in public investment, which might boost future productivity. Public gross fixed capital formation is about 5.6% of GDP, only a little above recent levels and below the long-run average. Instead, the increase in demand is overwhelmingly from government consumption, which is now around 23.3% of GDP.

With services inflation still running at 4.1%, that's an ugly policy mix. Higher rates into sticky domestic inflation, with fiscal policy acting as a tailwind, is a recipe for stagflation.