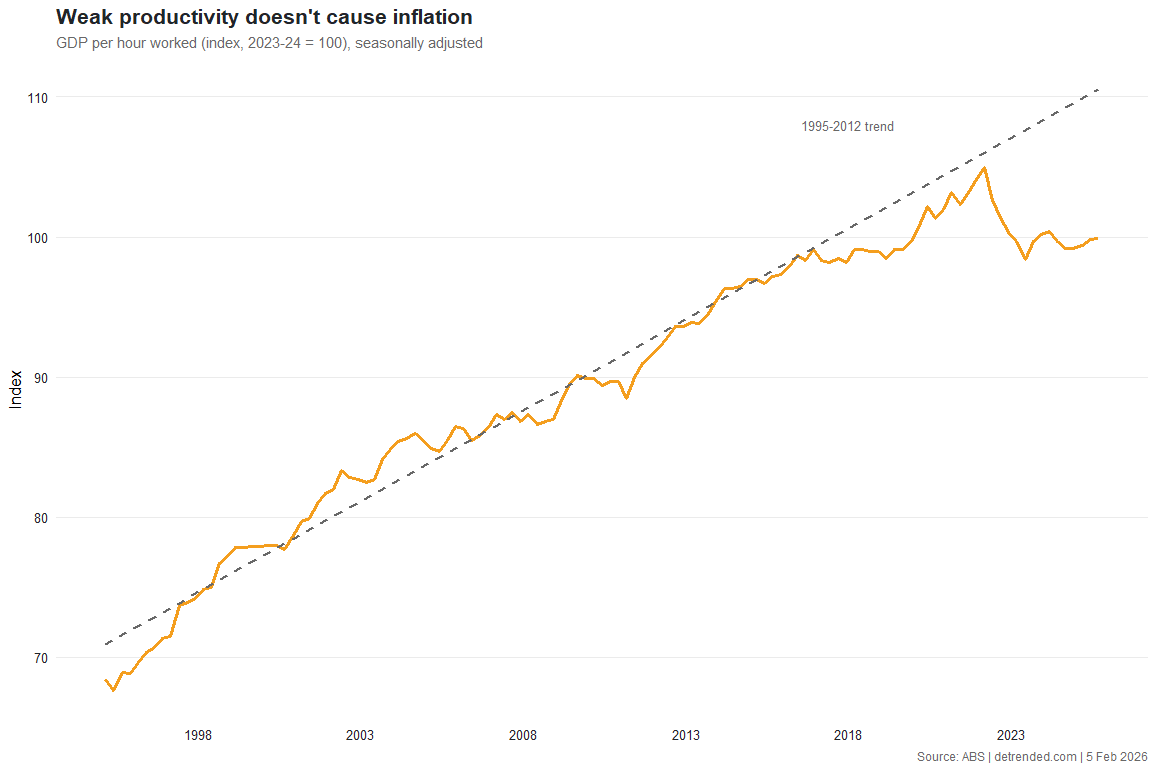

Weak productivity doesn't cause inflation

Monetary policy, not productivity, determines inflation.

As almost everyone expected, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) hiked rates earlier this week in the face of persistent inflation. In her statement, Governor Michele Bullock offered an explanation for why Australia's inflation problem just won't go away:

"The economy is closer to its supply capacity than we previously thought, which means supply constraints are binding in some more sectors and has not taken much of a pick-up in demand to generate price pressures. Years of weak to no productivity growth is a big part of that story."

She's not wrong. Productivity growth has been weak. Private and public demand have been robust. But as an explanation for why the RBA keeps missing its inflation target, it's a bit rich.

Australia's labour productivity (GDP per hour worked) is where it was nearly a decade ago, creating the "closer to its supply capacity" scenario that Bullock was talking about. But while weak productivity can change relative prices, it doesn't mechanically generate years of above-target inflation. It also isn't new; the RBA has had these data the entire time.

Let's be clear about what the RBA's job actually is: it sets the stance of monetary conditions, which shapes expected nominal spending growth economy‑wide.

It can only influence employment and real activity in the short run. It doesn't control productivity. It doesn't set zoning laws, run the education system, or decide how many forms you need to fill out to hire someone or start a project. It sets monetary policy, and monetary policy is the main determinant of the medium‑run inflation trend. Put differently: if nominal spending growth is running hot relative to the economy's capacity to produce, sustained inflation is the predictable outcome—and fixing it is the RBA's job.

If supply capacity is "constrained" due to weak productivity, then hitting its 2.5% midpoint inflation target requires tighter policy than it would in a high-productivity world. That's not an excuse for missing the target; it's literally the information the RBA must incorporate. Inflation targeting is conditioned on the supply environment, not suspended by it.

If demand was "stronger than expected" and financial conditions "eased" and credit growth picked up, those aren't purely exogenous shocks that just 'happened' to the RBA; the central bank's own stance and communications are part of why financial conditions ease or tighten. Saying "it's not taken much of a pick-up in demand to generate price pressures" when you're in charge of the institution responsible for managing demand is not the defence Bullock thinks it is.

Now to be fair to Bullock, she's not entirely wrong to point fingers elsewhere. State and federal fiscal policy has been working against her by propping up nominal demand, adding to the work monetary policy must do to get inflation back to target.

But central banks don't get to choose their operating environment. The RBA's mandate is price stability given whatever fiscal and structural conditions exist in the real economy. Weak productivity and loose fiscal policy mean you need tighter monetary policy to hit the same inflation target. That's the job description.

It's now 2026 and inflation has been outside the RBA's 2-3% target band for years. At some point, serial forecast errors stop being bad luck and start looking like an implicit choice: in this case, preferring a slower return to target and a higher rate of inflation over the tighter stance that's actually required in a low-productivity, fiscally-expansionary environment.